Abstract.

This is an expanded version of a paper originally given at the English and Theatre Studies research seminar at Melbourne University in May 2015, and it retains its oral tone. My intention both for the original paper and for this expanded version is to provide a first introduction to the work and thought of Michel Serres. I discuss how Serres’s work has been received in the French-speaking and English-speaking worlds to date, briefly highlight the different areas in which his thought is making a decisive contribution today, and then offer reflections on what it is that characterises his writing as a whole. I finish by examining some of his recent thought in more detail, specifically his recent elaboration of an econarratology around the idea of the “Great Story” of the universe, opening the way, for the first time in history, to develop a truly universal humanism.

Introduction

This is the start of a project. I am at the beginning of a journey with Serres and in this talk I want to share with you some of what drew me to write a book on him and where my research has led me so far. The first half will be a general introduction to Michel Serres’s thought, which means that it will inevitably be a mile wide and an inch deep. In the second half I will focus on a set of questions that arise in some of Serres’s recent work on humanism. Think of it as a selection of jelly beans followed by a steak. I will try to keep the technical philosophical work in the paper to a minimum and show how Serres can be useful to scholars across the disciplines.

Part A: An Introduction to Michel Serres

Biographical sketch

Michel Serres was born in 1930 in Agen, in the rural Aquitaine region of south-west France. He entered the Ecole Normale Supérieure, that great finishing school for French philosophers, in the same year as Jacques Derrida, and the two corresponded during their time at the ENS. In fact, they went on a skiing holiday together in 1953, during which Derrida met his future wife Marguerite. Derrida and Serres were two of only four students to take philosophy that year, though Serres’s main subject was mathematics. He spent 1956-8 in the French navy, during which time he served in the operation to reopen the Suez canal and in the Algerian war. From 1958-1968 he took up a lecturing post at the university of Clermont-Ferrand, where he was a colleague of Foucault at the time Foucault was working on The Order of Things. During this period he also made a three-part television series with Alain Badiou in 1967, entitled “Model and Structure”. In 1968 he moved to the new experimental university in Vincennes where he was succeeded in 1969 by Gilles Deleuze. He moved to a post at Paris I (Panthéon-Sorbonne) and in 1984 became professor in the Department of French and Italian at Stanford University. In 1990 he was elected as one of the forty members of the Académie Française, the highest honour in French intellectual life. Serres has written over seventy single-authored books, including two recent best sellers in France: Petite Poucette (translated on Thumbelina) on our technological culture, which sold over 100 000 copies in its first year, and Temps des crises (Times of Crisis) on issues relating to the financial crisis of 2008. He continues to publish today at the rate of just over a book a year. For those interested in his bibliography, there is a comprehensive list of publications on my website, as well as a timeline of his life and publications.

Reception of Serres’s work in France and the English-speaking world

To say that Serres has written over seventy books, his reception has been slight up to date. It is a corpus waiting to be discovered and mined, especially in the English-speaking world. But if we dig below the surface it turns out that the story of his reception is a little more complicated than that. Curiously, his work is cited a great deal without Serres himself being in the philosophical limelight.

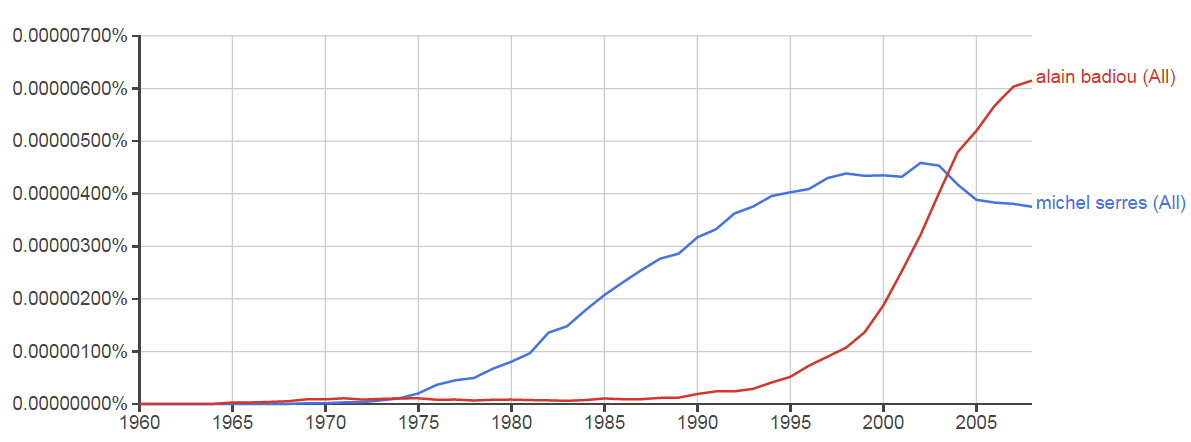

Here, for example, is a graph, generated from the corpus of google books, of the number of times Serres and Badiou are mentioned in books in French, published from 1960 to 2008 (the data stops in 2008):

And if we look at books published in English, we get this:

I make no claims for the statistical rigour of these graphs, and the only points I want to make from them are that 1) since 1960 Serres has been, and continues to be, mentioned by name in more French publications than his much better known contemporary Alain Badiou, and 2) he has been much more adequately received in the French speaking world than in the English (by a factor of roughly 10 to 1 as a percentage of all books published in the language a particular year). Serres largely remains to be discovered by English readers.

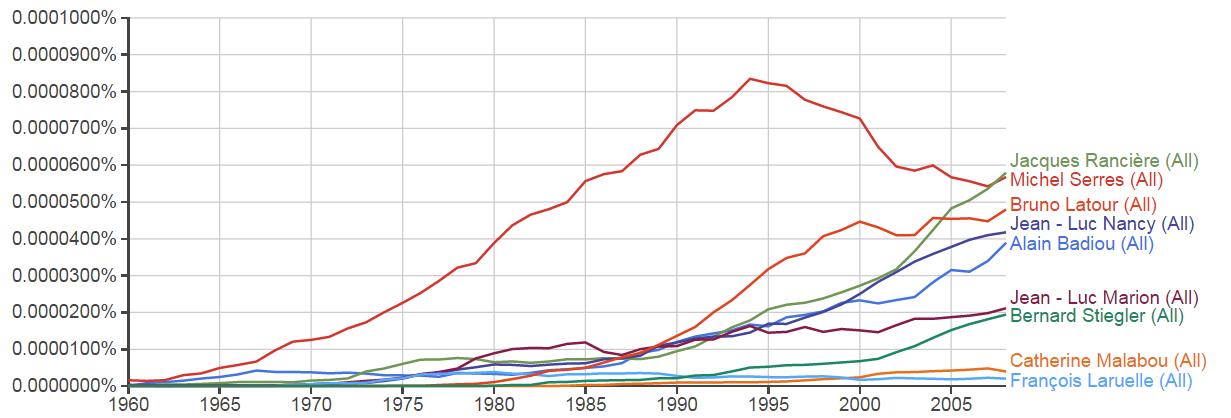

If we add in some other contemporary French philosophers we get the following trends for French-language books:

And these trends for English language publications:

What is striking in the French graph here is that, until around 2006-2007 Serres was far and away the most cited French philosopher still living in 2015, at which point he was just pipped by Jacques Rancière. Over a number of decades he has enjoyed a greater and more sustained citation count than other living French philosophers in Francophone publications, though again this is not yet reflected in the English-speaking world.

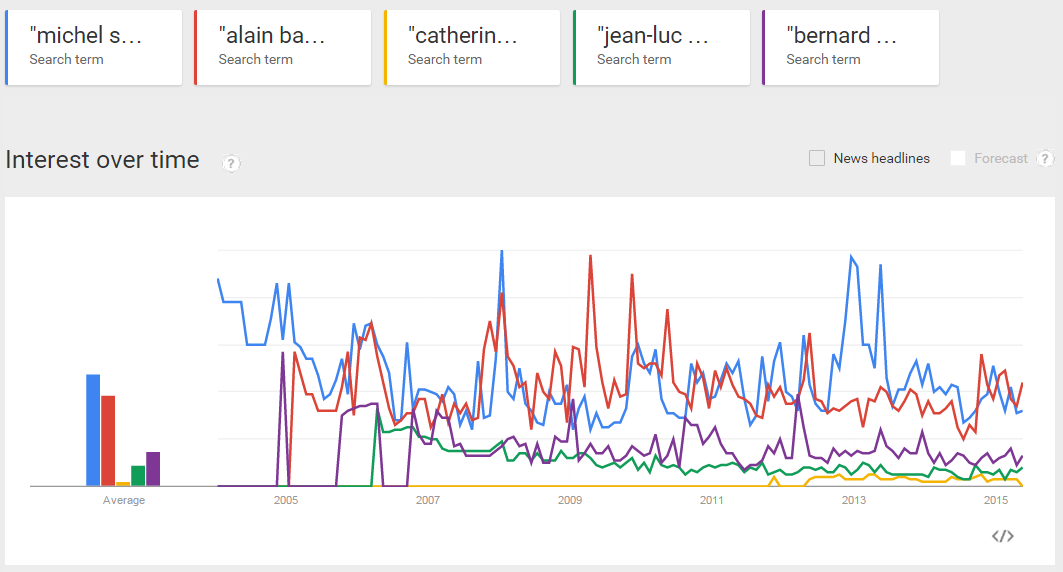

One final graph. If we look at Google Trends (i.e. what people are searching for on the web) again we find an interesting result:

Averaged over the period from 2005 to the present day, internet activity for Michel Serres is higher than for other living French philosophers; only Badiou comes close.

Averaged over the period from 2005 to the present day, internet activity for Michel Serres is higher than for other living French philosophers; only Badiou comes close.

However, despite these consistently high ratings by comparison with other contemporary French thinkers, there are only three existing monograph studies of aspects of Serres’s work (either in English or in French), four volumes of collected essays including one on Serres and Deleuze, and a handful of special issues of journals and journal articles. I think it is safe to say that, thus far, Serres has been somewhat under-received. If he is cited and mentioned so much, why is he not better known? William Paulson, who has written on Serres, offers one possible explanation:

Serres’s writing may be called utopian in that it calls on an audience that may not exist in any place, or that is so dispersed, at any rate, as not to make up one of the identifiable groupings we call cultural communities.”[1]

In other words, the range of subjects and disciplines within which and about which he writes is so broad that all those with an interest do not gather together as a group of “Serresians”. Whereas Serres himself manages to cross disciplinary boundaries, the community of his readers has not shown itself to be so courageous. A related reason for Serres’s slight reception is that his thought covers so great a breadth that it requires any reader to be ready to leave their disciplinary comfort zone if they are to engage with it.[2] It is partly this cross-disciplinarity that draws me to Serres, and I will talk more about it later.

How is Serres being used today?

The first thing to say here is that Serres is being used more and more. The translation of his books is really taking off now, with Bloomsbury in particular making more and more of his work available in English. There are a number of reasons why Serres’s work is being translated at an increasing pace now, and a number of reasons for thinking that his time has now come. I will point to four contemporary debates that are currently drawing heavily on Serres’s writing.

Posthumanism

A translation of Serres’s The Parasite was the inaugural volume in the Minnesota University Press “Posthumanities” book series, which billed it as “The foundational work in the area now known as posthuman thought”. In The Parasite Serres argues that human relations are not to be figured in the first instance in terms of mutual exchange but of parasitism. Every relational structure, whether human or non-human, Is parasitical. To suggest that the human is parasitical upon the non-human world strikes a decisive blow to the human non/human dichotomy, reframing the human not as the master and possessor of nature, nor as the Cartesian or phenomenological origin of the world, but as a second thought:

And that is the meaning of the prefix para- in the word parasite: it is on the side, next to, shifted; it is not on the thing, but on its relation. It has relations, as they say, and makes a system of them. It is always mediate and never immediate.[3]

Ecology and the environmental humanities

Serres is also at the forefront of the growing interest in ecophilosophy or the environmental humanities, largely through his 1991 book The Natural Contract. In this important book he insists that we cannot ignore that human interests and the interests of the planet are more intricately intertwined than ever, and that we cannot hope adequately to address the problems that face us today if we consider them if we consider them first and foremost as human issues. How can we hope to address climate change, for example, if we remain within an anthropocentric frame? We must find a way of taking all interests—human and non-human—into account, and Serres’s natural contract is a proposal to achieve this aim. Just as the social contract is an ideal framework for the regulation of human society in which all its members agree to certain norms of respect and behaviour, so the natural contract extends this regulatory ideal to make it adequate to the problems and issues that face us today, many of which surpass the merely human or cultural world. To the objection that the world’s oceans or forests cannot meaningfully enter into any agreement, Serres asks the objector to show him the original signatures on the social contract. The nature of the issues we face today means that we must give the non-human its place at the table.

New materialisms and object-oriented thought

Serres is also foundational reference for the emerging trends of new materialism and object oriented philosophy, partly in his own name and partly through the formative influence he has had on the thought of Bruno Latour.[4] Serres insists on a break with the linguistic philosophy of the late twentieth century, decrying any theory that is empty of objects and deals only in words.[5] A keen mountaineer and ex sailor, Michel Serres’s own sensibility for the natural world runs through his writing; his own philosophy has with the wind in its hair and soil under its finger-nails.

He has exerted a particular influence on object-oriented thought his refusal of the Cartesian subject-object dichotomy and his account of what he calls the quasi-object. One of Serres’s own examples of a quasi-object is the ball in a soccer game. Neither simply natural nor entirely cultural, the ball circulates among the players in a way that makes possible a certain set of social relations. It is misses something important, Serres argues, to characterise the ball as an inert object at the whim of the human subjects in the situation; it shapes and opens possibilities for their actions just as they do for its actions. Other examples of quasi-objects would be the smoking pipe passed from hand to hand and lip to lip, or the coin or note that circulates to facilitate economic relations, or words themselves, without the circulation of which human relations as we know them would be unthinkable.[6]

Cross-disciplinarity

Finally in this brief survey of ways in which Serres’s thought is being used today (though there are other areas of influence I have no time to mention today), he is influential through the way his work is genuinely cross-disciplinary and bridges the arts, humanities, social sciences and hard sciences. Serres, as I said, was trained as a mathematician and in one interview identifies his discipline as history of science. Unlike some would-be cross-disciplinary thinkers, he has earned his hard scientific chops. But Serres offers us no quick and easy interdisciplinary gesture or a casual nod in its direction. Throughout his career he shows a deep commitment to genuinely cross-disciplinary study.

One image that Serres uses to describe the difficulty of cross-disciplinary study comes from his own naval past and his passion for navigation. It is the North-West passage, that complex course from the Atlantic to the Pacific between Greenland and Canada. It is a true connection, but it is not a linear or straightforward one.

It is in terms of this local, painstaking navigation that Serres works through what it means to engage in cross-disciplinary study. Crossing the borders between academic disciplines cannot be simple, off-the-shelf or linear. This only leads to selling out one discipline to the assumptions or the methods of another, which is what all too often passes for interdisciplinary study today. For Serres, by contrast, cross-disciplinary work must be a careful, labyrinthine and bespoke navigation of the local, complex and unique relations between different fields:

The passage is rare and narrow […] From the sciences of man to the exact sciences, or inversely, the path does not cross a homogeneous and empty space. Usually the passage is closed, either by land masses or by ice floes, or perhaps by the fact that one becomes lost. And if the passage is open, it follows a path that is difficult to gauge.[7]

And

Passages exist, I know, I have drawn some of them in certain works using certain operators […]. But I cannot generalize, obstructions are manifest and counter-examples abound.[8]

One quick example of the sort of cross-disciplinary insights Serres seeks to bring to bear in his writing is his discussions of thermodynamics in the nineteenth century in the wake of Sadi Carnot’s discovery of the principles that would later be formalised as the second law of thermodynamics and entropy. Every metaphysics needs its physics, Serres argues, and we can see the principles of thermodynamics through the whole of nineteenth century culture:

Read Carnot starting on page one. Now read Marx, Freud, Zola, Michelet, Nietzsche, Bergson, and so on. The reservoir is actually spoken of everywhere, or if not the reservoir, its equivalent. But it accompanies this equivalent with great regularity. The great encyclopaedia and the library, the earth and primitive fecundity, capital and accumulation, concentration in general, the sea, the prebiotic Soup, the legacies of heredity, the relatively closed topography in which instincts, the id, and the unconscious are brought together. Each particular theoretical motor forms its reservoir, names it, and fills it with what a motor needs. I had an artefact, a constructed object: the motor. Carnot calls it the universal motor. I could not find a word, here it is: reservoir. […] Question : in the last century, who did not reinvent the reservoir?[9]

Serres sees a similar pattern in the twentieth century with information theory and code: the unconscious is structured like a language, the “secret” of life is found in the genetic code, and structuralism and post-structuralism both employ an encode-decode model of language, also taking on information theory’s ideas of noise, indeterminacy and interference.[10] As René Girard says of Serres, “criticism is a generalized physics”.[11]

What are the general characteristics of Serres’s thought?

So those are some of the main ways in which Serres is being deployed today in contemporary debates. My next question is: how are we to characterise his thought? What is its overall shape; what are its characteristic moves? It is a difficult question because 1) he eschews the predictability of repeating the same moves and 2) shape and space are themselves important themes in his thought. Nevertheless, I think there is something useful that can be said in this regard.

1) An encyclopedic method

Grant me for a moment that we might understand philosophy in general, and the history of French philosophy in the last century in particular, as a series of attempts to come to terms with the relation between system and singularity.[12] Let us think of these attempts in terms of two broad tendencies, which I shall call “system philosophies” and “singularity philosophies”. “System philosophies” seek to bring apparently diverse phenomena, objects or ideas under general explanatory concepts, finding the unity hidden behind seeming multiplicity. Where seeming exceptions to such systematisation exist they need to be explained away or incorporated into the system. Examples of this tendency might be Parmenides, the Scholastics, Descartes, Hegel and Sartre: fitting all facts and all phenomena into a comprehensive and overarching matrix and set of categories. The caricature of this philosophy is that it is a top-down imposition: it flies at an altitude of 30 000 feet and shoe-horns individual facts and phenomena into a universal matrix that emerges at such a level of abstraction. This sort of thinking will often seek the universal or the general principle. It is a philosophy of the same.

On the other hand we have “singularity philosophies”, which refuse systematisation and denounce over-arching concepts, rejecting the idea that behind apparent diversity lurks a more fundamental unity. These philosophies insist upon singularity and uniqueness: at their most acute, they claim that everything is always already an exception to every universal rule or category to which we might wish to assign it, and to insist on such rules is a violent imposition akin to racial stereotyping. We might think perhaps of Heraclitus, Pascal, Kierkegaard or the Nietzsche who said “I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity”.[13] This singularity philosophy emphasises the individuality, the contrariness, the unclassifiable recalcitrance of things. It is not a philosophy of the same but a philosophy of difference, and its rallying cry could be Derrida’s insistence that “every other is altogether other”.[14]

It is interesting to note that these two extremes also account for the factors that lead to philosophical celebrity, for each of them embodies one of the traits that tend to draw a crowd of acolytes round a particular philosopher and make a name for them. On the one hand, system philosophers draw a following by offering a powerful explanatory matrix able to account for what otherwise would be a bewilderingly disparate and confusion melee of phenomena, events and facts. Put somewhat crudely, you always have something clever to say about the evening news because you can explain it – and indeed you can explain everything – in terms of the system offered to you by your favourite system philosopher or philosophers: “well, of course, what’s really going on behind in these events is such and such, but of course most people just don’t realise that. How naïve! Good job we know better.” On the other hand, singularity philosophers build up an enthusiastic following by out-critiquing those who went before them, by out-suspecting all previous suspicion, exposing all previous critical philosophies as incomplete or flawed and thereby proclaiming themselves “more sceptical than thou”, until, inevitably, the philosophy in question is in turn knifed in the back by its successor: “The previous generation thought they were being anti-metaphysical, but what they failed to take into account of course was such and such, which made them by all accounts the last metaphysicians. How naïve! Good job we know better.”

Where does Serres sit in relation to philosophies of system and philosophies of singularity? In truth, he has no interest either in elaborating the system which will yield the truth of everything where before there has been only ideology and confusion, nor in being more critical and sensitive to difference than those who have gone before him. That is perhaps one reason why there is no Serresian school in philosophy full of little Serresians knowingly spouting the soundbites of their master. I think it is a healthy feature of his reception, and long may it continue.

For his own part, Serres charts a middle course between the Scylla of systematisation and the Charybdis of exceptionalism, a course he sums up with the motif of the encyclopedia. First, an encyclopedia ranges over the full extent of human and nonhuman existence, taking in all disciplines. In the same way, Serres’s thought has the ambition of stopping at every port, visiting every city. In one interview he insists that “A philosopher does everything, otherwise he does nothing”.[15] Secondly, in ranging over everything an encyclopedia does not pretend to exhaust anything, or to give a complete account of any subject it treats. Thirdly, an encyclopedia is not a system. It does not impose a matrix of interpretation from above, but each article approaches its subject in its own terms, often by different authors. It brings subjects together not through top-down fiat but in a bottom-up way, drawing local links and cross-references between ideas. It does not impose categories from outside but traces isomorphisms and equivalences from within.[16]

An encyclopedia is adequately characterised neither as a system nor as a generalised exception to systematisation. In Serres’s own words:

Philosophy has the job of federating, of bringing things together. So analysis might be valuable, with its clarity, rigour, precision and so on, but philosophy really has the opposite function, a federating and synthesizing function. I think that the foundation of philosophy is the encyclopaedic, and its goal is synthesis.[17]

Or again, it is the philosopher’s job “to attempt to see on a large scale, to be in full possession of a multiple, and sometimes connected intellection.”[18] In short, Serres’s encyclopedic approach is a way of seeking connections not from the air but by sea. Or again, Serres characterises his own work as an eighteenth century salon, bringing the disciplines together in a conversation that respects the integrity of each, not like a modern university, dividing them and often making them compete with each other.[19] Or, in one final image:

What I seek to form, to compose, to promote – I can’t quite find the right word – is a synthèse, a confluence not a system, a mobile confluence of fluxes. Turbulences, overlapping cyclones and anticyclones, like on the weather map. Wisps of hay tied in knots. An assembly of relations. Clouds of angels passing.[20]

2) The decline of the paradigm of consumption and the rise of the paradigm of communication

The second way in which I would like to characterise Serres’s thought today is that he rejects the prevalent paradigm of production and consumption in favour of the paradigm of communication. We might think of this as the great wager of his thought. Back in the 1950s he wagered that structuralism and all the philosophy that would come in its wake went down a wrong track when it reasoned in terms of a paradigm of production and consumption inherited from Marx:

at the end of the war, Marxism held great sway in France, and in Europe. And Marxism taught that the essential, the fundamental infrastructure was the economy and production: I myself thought, from 1955 or 1960 onwards, that production was not important in our society, or that it was becoming much less so, but that what was important was communication, and that we were reaching a culture, or society, in which communication would hold precedence over production.[21]

What does Serres mean when he says that production was becoming less important? He is drawing attention to what he calls the greatest revolution in human society since Neolithic times. Ever since the beginning of the Neolithic around 10 000 BC when humanity settled down and started planting crops, we have been in a culture most of whose members are involved in the production and consumption of primary goods, mainly foodstuffs. In Switzerland, Germany, France and Italy in the year 1900, 70% of the population worked the land. In the last century, however, that age-old pattern has seen a dramatic change. Today, in the same countries, less than 1% of all workers are involved in agriculture. For Serres, that is the greatest change that we have seen to human society in the last ten millennia, greater than the Renaissance, and greater than the two World Wars.[22]

Most of us today do not work in the production of primary materials; we circulate information. Furthermore, this circulation of information works according to a fundamentally different paradigm from that of production and consumption. Think of it this way (to use an illustration Serres sketches in one of his radio broadcasts): If you grow and harvest wheat and bake bread, and if I pay you five dollars for the loaf you have baked, then you have five dollars and no loaf, and I have a loaf but have lost five dollars. An exchange has taken place, on the basis of a process of production, and you and I find ourselves in a relationship of production, consumption and exchange. But that is not how it works with information. When I give a lecture on a French film or a French philosopher I do not have to forget that information in order for my students to remember it. It is not an exchange but a propagation. It is not a zero sum game. Of course it may be couched within the framework of mechanisms of exchange—the university takes money off the students and gives some of it to me—but that exchange is extrinsic to the propagation of information in the lecture, it is not essential to the nature of communication itself. In their essence, production/exchange and communication/propagation function very differently.

Back in the 1960s Serres wagered that our Western, industrialised society would increasingly be characterised by the propagation of information, not by the exchange of goods. Surely he was right: We have seen a rapid decline in primary industry in the West, of which my own childhood serves as a poignant example. When I was little, at the end of the road where I grew up was the huge Manvers colliery and coking plant. I have only vague memories of the winding towers and chimneys now, but my parents tell me that on some days the wind would blow the smoke and soot up the hill from the coking plant to our house and washing hanging out on the line would gather little black specks. Here is a picture of the Manvers complex from 1980:

The coking plant was closed in 1981, and the colliery in 1988. What stands on the site now is, in part, a complex of call centres:

The same story was repeated all over the coal mining areas of the north of England. The Sheffield steel industry similarly shrank to a small-scale high-end premium operation, while the same period saw the dramatic rise of communication and data processing technology from fixed to mobile phones and computers, for which the paradigm of production is no longer adequate. It is a trend that the complex of technologies we call “the internet” has only accelerated, and which is vividly exemplified in the loosing battles currently being fought by corporations over DRM and the free spread of information. The wager that Serres made in the 1950s is currently being vindicated along the fibres of the internet.

For Serres, Marxism and the philosophies that rely on its insights cannot account for this new reality of our society, because they still assume a paradigm of production and exchange whereas in fact more and more areas of society operate according to a paradigm of communication. It is not that production, consumption and exchange are going to die out—of course not—but that they no longer adequately describe how our society works.

That brings to a close the jelly bean part of this talk, seeking to range over Serres’s significance and give a thumbnail sketch of some overall shapes of his thinking. For the rest of my time I want to descend to ground level and look more carefully at one aspect of his ecological thinking.

Part B: Serres’s Econarratology

In a series of four recent books on humanity and humanism,[23] Serres makes a threefold claim:

- now, for the first time in history, we can elaborate a truly universal humanism

- we can do this by telling the story of humanity as part of a larger narrative of the universe

- this larger narrative is told not by human beings about the universe but told by the universe about itself

Let’s begin with the first claim: a truly universal humanism. For the first time in history, he argues, we now have the opportunity to do justice to the universality of the term “humanism” because “for the first time in the millennial process of hominization we have the scientific, technical and cognitive means […] to give it a federating and non-exclusive content worthy of its name”.[24]

What he has in mind here is that palaeoanthropology has unearthed partial skeletons, older than any recorded and culturally-specific history, of our earliest human ancestors, the “Lucys”[25] of the east African savannah whose descendants would spread throughout the globe. These discoveries give us a way to trace back the thread of time to a moment before the birth of recorded history and before the emergence of distinctive cultures within that history:

Our wisdom now places Lucy before Pliny the Elder, the bones scattered in the valleys of Chad before Blind Homer and Noah the vine-dresser, and our African Mother and Father before Adam and Eve, before all ancestors venerated in all cultures; it reads the genetic code before the code of Hammurabi. Here it is a question of humanity, and not some evil off-white noise-box [bavard et méchant blanchâtre] despising the scarlet barbarian”[26]

This early record of humanity, he claims, is “written in the encyclopaedic language of all the sciences and […] can be translated into each vernacular language, without partiality or imperialism”.[27] A truly universal humanism must begin with this pre-historic moment.

The second claim is that this story of humanity is part of a larger narrative of the universe, which Serres calls “the Great Story” (le Grand Récit). The structure of this story is an extension of Serres’s earlier work in biosemiotics. In The Birth of Physics he argues, in information-theoretical terms, that meaning emerges as an aleatory, local deviation in the ‘window’ between two modes of chaos: monotony and white noise.[28] In the same way, in his later work he understands narrative in terms of the interplay between two elements: a relatively constant line (which in Rameaux he calls the format) and unexpected deviations in that line which he pictures as the kinks and twists of a branch. Like the information-carrying signal that sits on the spectrum between the chaos of monotony and the chaos of white noise, so also the growth of a story takes place under a double tension: the necessity of using pre-established forms in order to communicate in a way that can be understood, and an obligation to rupture, deviate from and remake these forms because simply repeating them would hold no message at all.[29] It is in the tension between format and variation that stories emerge, tracing a continuity, branch-like, through haphazard, contingent and chaotic points.[30] Like a growing branch, a developing story need have no final end point, predetermined or otherwise (we are a long way with Serres from the Aristotelian mythos, and also from any deconstructive weak messianism) , and though its eventual form may seem to have a certain retrospectively apprehended teleological balance, its growth is a series of contingencies. We must, Serres insists, quell the prophetic instinct to project the end of the story from its beginning as if a single intention held together its disparate parts, and instead force ourselves to think a repetition or rule without finality and without anthropomorphism.[31]

The Great Story is told by Serres retrospectively as a series of four major and contingent bifurcations in the branch that leads to human beings, four events each more ancient than the last. The first event already takes us back millions of years to the appearance on the planet of homo sapiens. The second event is the emergence of life on earth, from the first RNA with the capability to duplicate itself, through the three billion years when bacteria were the dominant life-form, to the explosion of multi-cellular organisms recorded in the Burgess shale and the huge proliferation of orders, families, genera and species. The third takes us back from biology to astrophysics and to the first formation of material bodies in an infant universe. When it reaches a certain temperature the ionisation that prevented certain particles forming nuclei ceases, and matter begins to become concentrated into galaxies separated by a quasi-void.[32] Finally, the fourth and most distant event is the birth of the universe itself, the origin of origins.

Properly speaking, these different stages in the story do not form a succession, as if each needed to stop for the next to begin. The universe is still cooling; the earth is still developing and new planets forming; life on earth, and quite possibly elsewhere, is still diversifying and proliferating, and human beings are still evolving. It is better not to think of a succession of chapters (and this is where Serres’ image of the branch is potentially misleading) but one story told by four voices in counterpoint, each successively joining the collective narrative at a specific moment. What unites these four voices for Serres is the idea of ‘nature’, understood etymologically as that which is born, that which marks a temporal distinction, a ‘before’ and an ‘after’. Nature is ‘a story of new-born events, contingent and unpredictable’.[33]

In passing, I want to draw two important consequences from Serres’s account of humanity as part of the Great Story. First, in Serres’s account humanity derives its identity from its place in the universal narrative, not from any biological or psychological capacity that may or may not mark the ‘difference’ between the human and the non-human, such as intelligence, rationality, language use or bipedalism. This allows Serres’ account refreshingly to avoid the interminable and often dangerous debates around what faculty or capacity might or might not ‘make human beings unique’, along with the liminal cases thrown up by such an approach: the senile, the neonate, and those with severe mental or physical disabilities. Whereas such an account of humanity based on supposedly distinctive human capacities advances by drawing more or less unsubstantiated divisions and erecting castles of hierarchy on the shifting sands of our current biological and psychological understanding, Serres’ narrative approach identifies the human by drawing it ever further into a story it shares with the rest of the universe, not in the first instance by arguing for its uniqueness.

The second consequence I want to draw here from Serres’s understanding humanity in terms of the Great Story is that it gives us a new understanding of culture. In an interview with Pierre Léna in the Cahier de l’Herne dedicated to his work, Serres draws two immediate consequences from understanding humanity in terms of the Great Story. First, it gives us a new sense of culture. Traditionally, a person would be thought cultured if they had some working knowledge of four thousand years of history, beginning either in Greece or Mesopotamia; when someone discovers fifteen billion years behind him he must change his thinking completely or, to translate Serres literally, “he no longer has the same head”.[34] This idea that humanity, when considered as part of the Great Story, no longer has the same head is true literally as well as figuratively. Serres repeats often that different areas of the human brain evolved at different times: the neo-mammalian neocortex, the paleo-mammalian limbic system and the reptilian basal ganglia.[35] This brings along with it a shift in the notion of narrative itself. What used to be the beginning of ‘history’ (usually thought to be coeval with the invention of written communication some four thousand years ago) is now shown to be the briefest of episodes arriving at the end of a much more ample narrative which, Serres claims, is recounted by the universe itself.

This brings us to the third of Serres’s three claims: the universe is not ventriloquized by humanity but it tells its own story. There is for Serres no imperialist, anthropocentric or animist imposition of human meaning-making and story-telling on the recalcitrant, indifferent or meaningless flux of life, no torturing of a helpless nature on the rack of merciless syntax. The universe, the earth and life know quite well how to tell the story of their own origin and evolution, and when I write I share in and draw upon the same resources.[36] We see here a marked difference from Badiou, Meillassoux and Malabou, all of whom (Meillassoux and Malabou explicitly) hold that the universe is indifferent to human concerns and that to ascribe to it human categories of meaning is an anthropocentric error. Serres’s position here in fact cuts against the grain of the great majority of the “linguistic philosophy” that held sway in the generation previous to Meillassoux, Badiou and Malabou, and against the grain of most modern thinking since Descartes. For Serres there is no substance dualism, no Camusian absurd, no Kantian noumenon, and as far as Serres is concerned it is no more anthropocentric to claim that the universe is meaningful than it is to claim that Romeo and Juliet is meaningful: they both participate in the same universal dynamic of growth and deviation. For Serres there is no such thing as brute, indifferent matter. The world tells its own story and all we need do is find the ears to hear it. As Steven Connor puts it, “coding, information, writing, goes all the way down, and all the way back”.[37]

It could be objected that claiming the world tells its own story is more cosmetic than substantial, because however far the Story may stretch back in time it still needs to be told through human investigation and in human language, and is still therefore a story told by humans and for humans which happens to ventriloquize the non-human. However, this objection assumes that human language emerges ex nihilo in the Great Story, which is precisely what Serres contests. In the same way that, in The Birth of Physics, Genesis and The Parasite he insists that semiotics are natural, so also in his elaboration of the Great Story he argues that narrative is an inherent feature of the “natural” universe, of the universe of natal events. There is no qualitative difference between the story of evolution and the story of the Odyssey: they both enact, each in their own mode, the processing, ordering and communication of information in an interplay between format and deviation.[38]

Serres had previously made the argument that all life (and beyond: Serres includes crystals) receives, processes, stores and emits information: “nothing distinguishes me ontologically from a crystal, a plant, an animal, or the order of the world”.[39] In the four books exploring the humanism of the Great Story he merely expands this biosemiotic analysis to encompass his new econarratology, describing this expansion with an image from aeronautics:

A four-stage rocket launches the birth of language, the emergence of the ego and the dawn of narrative which, in telling their story, forms and creates them but forgets their origin: first it bursts forth from heat towards white noise; from this brouhaha to the first signals; then from these to feeble melodies; finally from these to the first vowels… Noise, call, song, music voice… come before the basic form of enunciation, before the language of story.[40]

The world does not mutely wait for the advent of humanity in order to tell its story; things speak for themselves, write by themselves and write about themselves, performatively speaking their autobiography, or “autoecography”: “The universe, the Earth and life know how to tell the story of their origin, of their evolution, the contingent bifurcations of their development and sometimes let us glimpse the time of their disappearance. An immense story emanates from the world.”[41]

We get close to the heart of the matter, I believe, if realise that Serres’s metaphors are in fact synecdoches: he is not speaking of one thing in terms of a second, ostensibly unrelated thing but speaking of a whole in terms of one of its parts. One of Serres’ characteristic moves, and we see it here in his defence of metaphorical language, is to invert the order of our thinking so that elements we previously considered to be in a horizontal, metaphorical relation are in fact seen to be nested in a synecdoche. In the example we are presently considering, if we object that the rhythms of nature cannot properly be classed as a story in anything other than an anthropomorphising metaphor, Serres might reply that, rather than trying and failing to force the rhythms and events of the world into a mode of storytelling modelled on human syntactic prose (which would merely constrain them to become an ungainly extension of Aristotelian narrative) we should rather realise that the varieties of human storytelling are themselves already one local expression of a broader phenomenon which they neither exhaust nor inaugurate:

Must I find stories or confessions in the inertia of the living? When I write my own stories and confessions, do I realise that, as a fractal fragment of the universe, I am imitating galaxies, the planet, masses of molecules, radioactive particles, the bellowing of a dear or the vain unfurling of a peacock’s plumage?[42]

In other words, the idea that nature tells its own story is not an unwarranted metaphor; on the contrary, “storytelling” understood as a human cultural practice is already a synecdochic expression of a much more widespread natural phenomenon. When I write, I write like the light, like a crystal or like a stream; I tell my story like the world. A frequently cited phrase from Serres’ The Birth of Physics has until now always been translated as “History is a physics and not the other way round. Language is first in the body”.[43] However, this translation collapses the multivalence of the French histoire, and the sentence could equally run “Story is a physics…”. In fact, both senses of “histoire” are at play in Serres’ discussion of negentropy in The Birth of Physics.

The change of paradigm from the metaphorical to the synecdochic is also a challenge to anthropocentrism. To see eco-narratives as a metaphorical extension of human storytelling is to assume that human storytelling as the non-metaphorical yardstick by which all other putative narratives must be measured. But to see human storytelling as a synecdoche of a much broader phenomenon is, as Serres remarks, to decentre narrative with relation to the human at the moment when nature wrests from us our claim to an exclusivity of language use.[44]

In conclusion, Serres’ econarratology allows us to think the universe not simply as a blank canvas for the quintessentially human practice of storytelling, but as the narrator of its own story. This means that, just as narrative identity allows us to think human identity beyond the possession of determinate capacities (like language or rationality) and beyond the limit of the human and the non-human, so also Serres’s ecological narrative identity frees us from having (falsely) to identify the universe as an inert and passive collection objects inviting human manipulation and exploitation, and a blank canvas waiting to be daubed with our ex nihilo human meanings.

This paradigm shift has the power to enrich the dialogue between the arts and the sciences at a moment when the global issues that face us are increasingly irreducible to the human scale, and to expand the study of narrative identity beyond its customary anthropocentric limits. In his insistence upon the Great Story of the universe, I would argue that Serres has indeed presented the study of humanity across the human and natural sciences with a valuable tool and a productive way of thinking.

NOTES

[1] William Paulson, “Michel Serres’s Utopia of Language”, Configurations 8:2 (2000) 217-8.

[2] This point is made by Pierpaolo Antonello when he argues that “Any academic who engages herself with Serres’s thought is then required to be a hybrid, to exceed the boundary of any established profession or discipline, to become an outsider.” Pierpaolo Antonello, “Celebrating a Master: Michel Serres”, Configurations 8:2 (2000) 167.

[3] Michel Serres, The Parasite, trans. Lawrence R. Schehr (Minneapolis, MN: University Of Minnesota Press, 2007) 38-9.

[4] See in particular Michel Serres and Bruno Latour. Conversations on Culture, Science and Time, trans. Roxanne Lapidus (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995).

[5] Michel Serres, “Panoptic Theory,” in Thomas M. Kavanagh (ed.), The Limits of Theory (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1989) 28-9.

[6]Michel Serres, Rameaux (Paris: Editions le Pommier, 2004) 158.

[7] Serres, Hermès V, 18. Quoted on Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” xi.

[8] Serres, Hermès V, 23-4. Quoted on Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” xiii.

[9] Michel Serres, La Distribution: Hermès IV (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1977) 60-1. Quoted in English translation at Josué v. Harari and David F. Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies”, inMichel Serres, Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982) xix.

[10] Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” xxiii.

[11] “Serres’s major interest is the parallel development of scientific, philosophical, and literary trends. In a very simplified manner, one might say that Serres always runs counter to the prevalent notion of the two cultures -scientific and humanistic-between which no communication is possible. In Serres’s view ‘criticism is a generalized physics,’ and whether knowledge is written in philosophical, literary, or scientific language it nevertheless articulates a common set of problems that transcends academic disciplines and artificial boundaries.” Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” xi.

[12] Not the many and the one or the singular and the universal.

[13] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols: And Other Writings, ed. by Aaron Ridley, Judith Norman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) 159.

[14] This phrase recurs a number of times in Derrida’s writing. See for example Jacques Derrida, Without Alibi, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002) 126.

[15] Michel Serres and Marie-Claude Martin, “Entretien: «Un philosophe fait tout, sinon il ne fait rien ».” Le Temps, 9 April 2011. http://www.letemps.ch/Page/Uuid/599bd724-6220-11e0-9818-ce393cc5d9d9/Michel_Serres_Un_philosophe_fait_tout_sinon_il_ne_fait_rien. Last accessed April 2015.

[16] This point is made on Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” xxxvi.

[17] Michel Serres and Raoul Mortley. “Chapter III. Michel Serres”, In French Philosophers in Conversation (ePublications@bond, 1991) 53. http://epublications.bond.edu.au/french_philosophers/4/. Last accessed May 2015.

[18] Michel Serres, Hermès V: le Passage du Nord-ouest (Paris : Editions de Minuit, 1980) 24. Quoted on Harari and Bell, “Journal à plusieurs voies” 13.

[19] Serres and Mortley, “Chapter III. Michel Serres” 59.

[20] Michel Serres and Bruno Latour, Conversations on Culture, Science and Time, trans. Roxanne Lapidus (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995) 122.

[21] Serres and Mortley, “Chapter III. Michel Serres” 51.

[22] The figures are quoted in Serres and Martin, “Entretien: «Un philosophe fait tout, sinon il ne fait rien »”.

[23] Michel Serres, Hominescence (Paris: Editions Le Pommier, 2001); L’Incandescent (Paris: Editions le Pommier, 2003); Rameaux (Paris: Editions le Pommier, 2004); Récits d’humanisme (Paris: Editions le Pommier, 2006).

[24] Serres, Hominescence 171-2. All translations of French texts as yet unpublished in English are the author’s.

[25] “Lucy” is the name given to the partial skeleton (about 40% complete) of a 3.2 million year old australopithecus afarensis discovered in Ethiopia by palaeontologist Donald C. Johanson in 1974. Until 2009, Lucy was the oldest substantial human ancestor skeleton yet discovered.

[26] Serres, L’Incandescent 196.

[27] Serres, L’Incandescent 32.

[28] Michel Serres, La Naissance de la physique dans le texte de Lucrèce: fleuves et turbulences (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1977) 181/The Birth of Physics, trans. Jack Hawkes (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2000) 146.

[29] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 154.

[30] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 153.

[31] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 188.

[32] Serres, Rameaux 115.

[33] Serres, Rameaux 115-6.

[34] Michel Serres and Pierre Léna, “Sciences et philosophie (entretien)”, In François L’Yvonnet and Christiane Frémont (eds.), Cahier de l’Herne Michel Serres, (Paris: Éditions de l’Herne, 2010) 55.

[35] See Pascal Picq, Michel Serres and Jean-Didier Vincent, Qu’est-ce que l’homme? (Paris: Les Editions du Pommier, 1999) 90; Peter Hallward and Michel Serres, “The Science of Relations: An Interview”, Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 8:2 (2003): 233; Serres, L‘Incandescent 23.

[36] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 80.

[37] Steven Connor, “Michel Serres: The Hard and the Soft”, A Paper Given at The Centre for Modern Studies, University of York 26 November 2009, 22. http://stevenconnor.com/hardsoft/hardsoft.pdf.

[38] Serres, Rameaux 178.

[39] Michel Serres, La Distribution: Hermès IV (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1977) 271/Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy 83.

[40] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 49-50.

[41] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 80.

[42] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 80.

[43] Serres, La Naissance de la physique 186/The Birth of Physics 150.

[44] Serres, Récits d’humanisme 80.