This the third of four undergraduate lectures in which I explore how the thought of Michel Serres can inform film studies. I embarked upon the lectures as a speculative experiment, but in writing them I became convinced that there are rich resources in Serres’s thought for generating novel and engaging readings of films that often depart from critical orthodoxy in productive ways, just as does Serres’s thought itself. I post the lectures here in their original form, reflecting the conventions and register of spoken delivery. My hope is that they can be a stimulation to scholars of film studies and scholars of Serres’s thought alike.

In this third lecture on Michel Serres and film I want to think with you about Trois Couleurs: Bleu, the 1993 film by Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski.

You don’t have to read much criticism about this film before you come across the language of trauma, loss and absence. It is common to read the film as an exploration of traumatic experience drawing on theories of trauma from Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. In terms of film studies, this understanding of trauma is perhaps most influentially set forth in Cathy Caruth’s 1996 book Unclaimed Experience, which reflects on trauma particularly in relation to literature:

You don’t have to read much criticism about this film before you come across the language of trauma, loss and absence. It is common to read the film as an exploration of traumatic experience drawing on theories of trauma from Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. In terms of film studies, this understanding of trauma is perhaps most influentially set forth in Cathy Caruth’s 1996 book Unclaimed Experience, which reflects on trauma particularly in relation to literature:

If Freud turns to literature to describe traumatic experience, it is because literature, like psychoanalysis, is interested in the complex relation between knowing and not knowing, and it is at this specific point at which knowing and not knowing intersect that the psychoanalytic theory of traumatic experience and the language of literature meet.[1]

What we find in the literature on Bleu is that this theory of trauma tends to colour the way people read the whole film. Everything is trauma, loss, and absence. Take, for example, Slavoj Žižek’s treatment of the film in The Fright of Real Tears. Let me read you a quotation, and then break it down:

Nothing renders her subjective stance better at this moment [disgust at the baby mice] than this aversion of hers, which bears witness to the lack of the phantasmatic frame that would mediate between her subjectivity and the raw Real of the life-substance: life becomes disgusting when the fantasy that mediates our access to it disintegrates, so that we are directly confronted with the Real, and what Julie succeeds in doing at the end of the film is precisely to restitute her fantasy frame.[2]

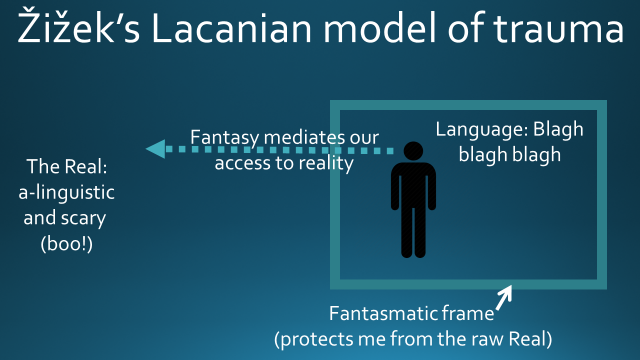

Žižek is employing a Lacanian model of trauma, that looks like this:

- We all live within what he calls a phantasmatic frame, that protects us from what Žižek and Lacan call “the Real”, the raw, unmediated, overwhelming outside that overflows and explodes all of our categories.

- Language, or what Lacan calls the symbolic, operates within the frame, and packages reality up into bite-sized and recognizable chunks for me, so that I am not overwhelmed by it.

- My access to “reality”, as I amuse myself to think of it, is a fantasy, not a direct access at all.

- So I am snug and protected within my phantasmatic frame. I feel that the world is comprehensible to me, because the world I inhabit is a world constructed by my powers of comprehension.

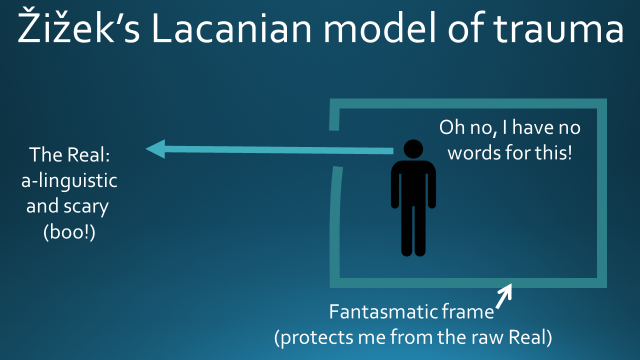

But what happens when the phantasmatic frame ruptures? Answer: overwhelming chaos, trauma and a breakdown in my capacity to comprehend and navigate the world. Like watching ten films in ten different languages all at once, at double speed and with the sound turned up to eleventy-stupid, I simply can’t process the assault I am faced with.

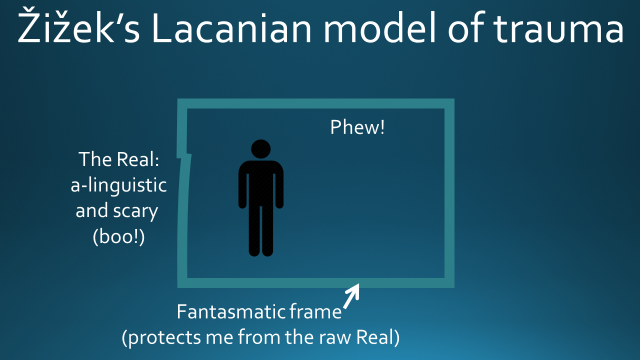

On Žižek’s reading, It’s disgust at a raw Real. By end of film Julie restitutes her fantasy frame. Once again she has ways of reducing the overwhelming complexity and rawness of reality, and living within the cocoon of her linguistically- and symbolically-mediated world, as we all do almost all of the time:

This restitution of the fantasy frame occurs in the film’s final scene, in which the Paulinian agape is given its ultimate cinematic expression. While Julie sits in bed after making love, the camera covers four different scenes in one continuous long shot, slowly drifting from one to the other (accompanied by the choral rendition of the lines on love from Corinthians I); these scenes present the persons to whom Julie is intimately related.[3]

In other words, at the film’s close Julie has done something like this:

In accord with this view of the film, critics fall over themselves to accumulate examples of trauma and loss in almost every scene and every line of dialogue:

This film is an incarnation of grief: its unwieldiness, lulls, rhythms, frightening unpredictability, bursts of aggression, nebulous sense of time, and utter emptiness. The film is a requiem composed in images. The grief here is also a close cousin to the longing exhibited in The Double Lfe of Véronique. It is another experience of absence — a space in one’s life vacated, a precious, foundational thing taken away. I know of no single film that so fully explores and articulates the dynamics of loss as Blue.[4]

Blue avoids flashback or any literal recovery of memory. The film as a whole is entirely faithful to its protagonist’s desire to live in the present, albeit a present whose temporal specificity is shattered. As Emma Robinson has put it so succinctly, the film’s subject is the ‘trauma of living in the present absence of the past’. Julie’s denial of the past, her emptying out of her past existence, entails involuntary absences for the viewer. […] Julie’s mind is arguably a space of absence, emptied out by her trauma, her perceptions and emotions are represented in various ways as external to her.[5]

We all know the relaxation training advice: in order to forget inner turmoil, focus on the outside, name voices and sounds, empty yourself. This is what Julie does – but what she gets from the outside are again messages about her inner trauma.[6]

This is the spectator’s entry into Julie’s consciousness: we know it only as site of trauma. Massive trauma precludes its own registration. The accident in which Julie’s husband and her unnamed daughter are killed cannot be known to her. In the blank screen, Blue testifies to an absence, a space which will fissure the film as representation. The film will remain split between intense subjectivity and the denial of vision.[7]

Let’s now take some specific examples of purported absences in the film, to which I plan to return later in the lecture.

The colour blue

First of all, the colour blue is seen as a symbol of trauma absence in the film, as Emma Wilson exemplifies:

We can never know whether Julie herself supposedly experiences these traumatic intrusions as blue light and music, or whether the film finds sensory analogues, the very raw materials of audiovisual representation, to connote her traumatized perceptions.[8]

Georgina Evans concurs:

The blue rectangle, previously the space of infinite, aching absence, is repopulated in the coda by the ultrasound image of Patrice and Sandrine’s unborn child.[9]

For Žižek, blue figures separation:

According to standard colour psychology, blue stands for autistic separation, for the coldness of introversion, of the withdrawal-into-self. Indeed, Blue is the story of a woman thrown into such a situation. Her traumatic encounter with the Real dissolves symbolic links and exposes her to radical freedom.[10]

Just note the final words of that quotation: “exposes her to radical freedom”. It is an idea to which I want to return, and one through which we will see a new perspective on the film open up.

Waking from trauma

After the colour blue itself, the second element of the film customarily read in terms of absence, loss and trauma is the scene in which Julie wakes up in hospital for the first time after the crash.

Wilson and Žižek again:

As the film emerges from this post-traumatic absence, the first images which appear seem formless and meaningless: fibres on cloth. The camera lingers in extreme closeup on these, and on their perceptible movements. It becomes possible to work out, a few shots later, that this is fluff on Julie’s pillow. These first images derive entirely from Julie’s point of view and angle of vision.[11]

The close-up of the eye in Blue stands for the symbolic death of Julie: not her real (biological) death, but the suspension of the links with her symbolic environment, while the final shot stands for the reassertion of life. […] The two shots thus stage the two opposed aspects of freedom, the ‘abstract’ freedom of pure, self-relating negativity, withdrawal-into-self, cutting the links with reality, and the ‘concrete’ freedom of the loving acceptance of others, of experiencing oneself as free and finding full realisation in relating to others.[12]

Music

Then there is the film’s music, which is also thought of as connoting negativity, trauma and absence:

back in Blue, are these intrusions of the musical past not in a way both at the same time, oscillating between symptom and fetish? They are returns of the repressed, yet they are also fetishistic details in which the dead husband magically survives.[13]

This is also the first time as viewers that we hear the music which is central to the film and which will echo in its spaces of denial. […] The music which appears to be the sound of her consciousness, the intense noise she hears unbidden, taking her into the place of her trauma, back before language, is audible to the viewer too.[14]

Swimming

On to swimming: another motif of trauma, absence and loss…

The visual motif of a woman swimming alone in a blue pool at night as the ‘objective correlative’ of her solitude and proto-psychotic exclusion from society is also used in Randa Haines’s Children of a Lesser God, to emphasise the (self-)exclusion of the embittered deaf-mute heroine.[15]

In the final visit to the pool, immediately after the shock of her first meeting with her husband’s pregnant lover, a splash indicates Julie’s arrival before the camera pans round the space. Through a deep blue filter, we see more of the building than ever before. The lens dwells on the lines running round the walls and door and between the lanes, the railings of the balcony and the innumerable rectangular dashes of the strip lights. The environment seems to hum with the resonant emptiness and threat of a Rothko painting as she faces the pain of betrayal by somebody who is not there.[16]

Synaesthesia

The final aspect of the film I will mention in relation to trauma, absence and loss is synaesthesia, a condition in which the stimulation of one sense triggers experiences related to other senses, for example smelling colours or hearing numbers.

Evans has a very negative view of how synaesthesia functions in relation to Julie’s character:

Bleu reinterprets nineteenth-century experiments with synaesthesia in art, their mystical practitioners and spiritual aims, to suggest a morbid detachment at the heart of such work. Julie’s synaesthesia becomes fused with her music as an isolating disease, to be cured only by an act of wilful rejection.[17]

She thinks that synaesthesia isolates Julie: “Kieslowski transforms this misanthropic nineteenth-century sensory gift, which sets the Parisian artist above the crowd, into something which sets Julie apart, in crippling isolation”.[18]

In all these aspects of the film, then, there is a reading which sees absence, trauma, loss, separation and isolation. But I want to begin by observing that—as we noted in relation to Cléo de 5 à 7 in the first of these lectures—this way of reading the film has to sweep some details under the carpet.

Here are some of the features that might cause us to look again at reading Bleu as a film about trauma:

- “Absence” and “emptiness”, in order to be recognised as such, rely on a constant remembering of the forgetting itself. The absence in question must itself be present, the emptiness must itself fill the consciousness, in order to be recognised as absent and empty. The problem in the film is not absence, but the crushing presence of absence.

- Loss, absence and passivity can feed into a discourse of victimhood which reinforces ideas of a passive femininity

- Synaesthesia is a condition of making unexpected links, of joining together the seemingly unrelated, of uniting the isolated. Synaesthesia transgresses limits and frontiers, whereas trauma creates an unbridgeable limit. This is a tension that is read into the film as it is pressed into the mould of contemporary theories of trauma (Caruth), and that it is not found of necessity in the film itself. Below I want to suggest a different reading of the film, one in which trauma and synaesthesia are not in tension.

- The trauma reading of the film has also run into difficulties with the film’s score. Take this passage from Žižek for example:

The weak point of Blue, the index of what is false about the film, is its musical score: the deceased husband had been commissioned to write a Concerto for Europe celebrating the unification of the continent, and this is the piece Julie finishes at the film’s end. This hymn, devoid of any ironic distance, which underlies the final synchronic Paulinian vision of love, is composed in the New Age style of Gorecki’s third symphony, inclusive of a funny reference to the non-existent seventeenth-century Dutch composer Budenmeyer. What if this apparent lapse in quality signals a structural flaw in the very foundation of Kieslowski’s artistic universe? This ridiculous and flat political background of a unified Europe cannot be dismissed as a superficial compromise, of no importance in comparison to the intimate process of trauma and gradual recuperation of the heroine: the post-political notion of a unified Europe defines the only social co-ordinates within which the ‘private’ drama of the heroine can take place.[19]

Marek Haltof, for his part, sees nothing but irony in the score:

Julie destroys her husband’s remaining compositions, including the unfinished musical score praising European unity, Concerto for the Unification of Europe (ironically, at the same time Julie desperately tries to disconnect from the world).[20]

As I suggested in relation to the temporal precision of Cléo two weeks ago, when anyone suggests that there is a “weak point” or “false note” in a film, it is always worth asking whether it may be that, rather than the film being at fault, it is their interpretative grid that is to be found wanting.

The final awkward point for the absence and trauma interpretation of the film is the difficulty it has in positioning Julie. For Žižek, we “fully identify” with Julie as “we experience the cold, distanced mode as expressing her own detachment”.[21] So is she utterly isolated, or do we fully identify with her? It seems that both of these statements cannot be true.

So let’s review the counter-examples to isolation and loss in the film: a symphony for European unity, synaesthesia, we completely identify with Julie, the necessity for absence to be present. There seems to me to be a good prima facie case for exploring the idea that there is more going on in this film than unmitigated loss and absence.

Reading Bleu with Michel Serres

This is where we turn once more to the thought of Michel Serres. Serres gives us a different model of trauma to the Freudian/Lacanian model of loss and absence, and it is one which helps us to see certain features of the films that the traditional model fails to make visible.

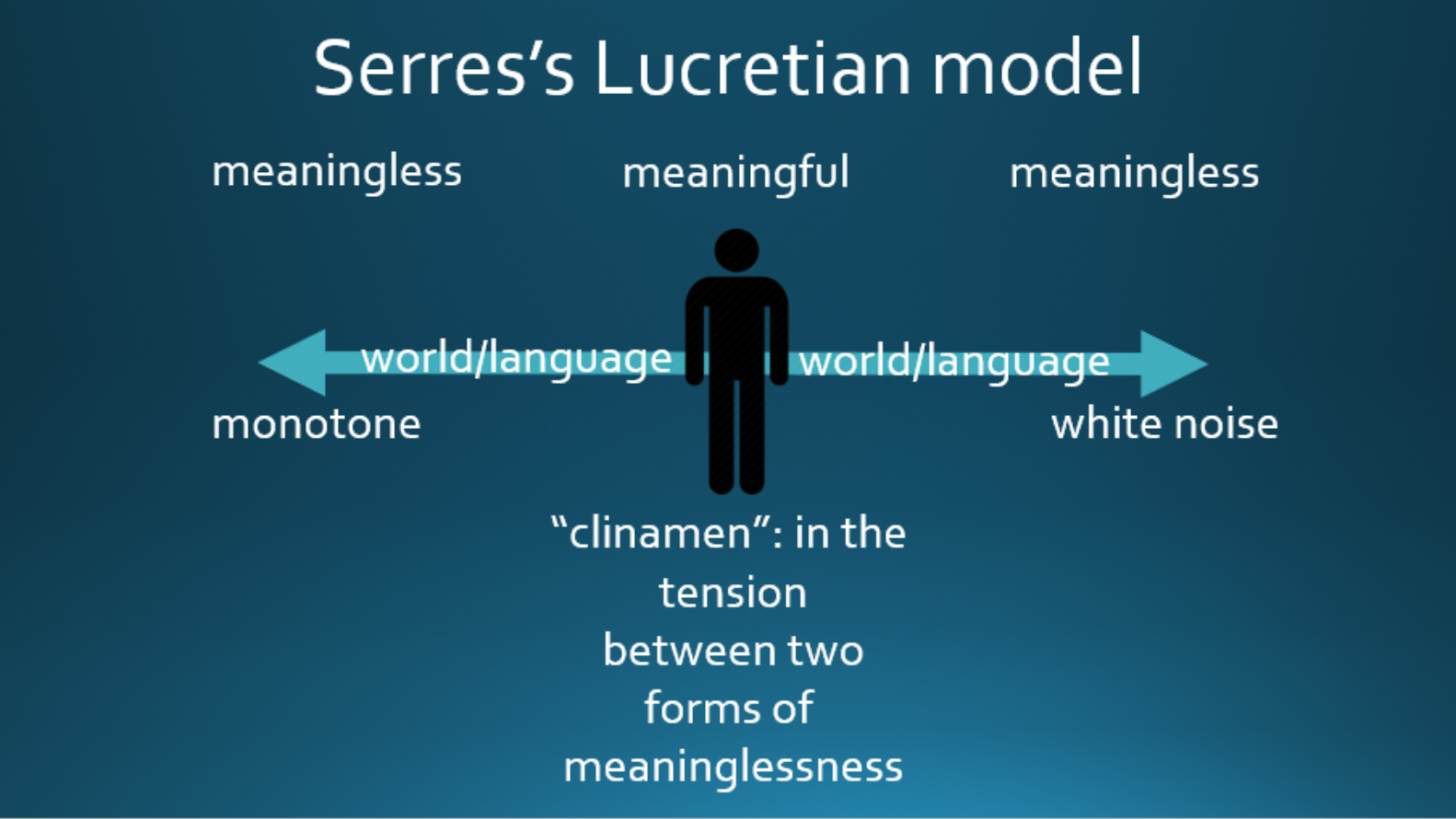

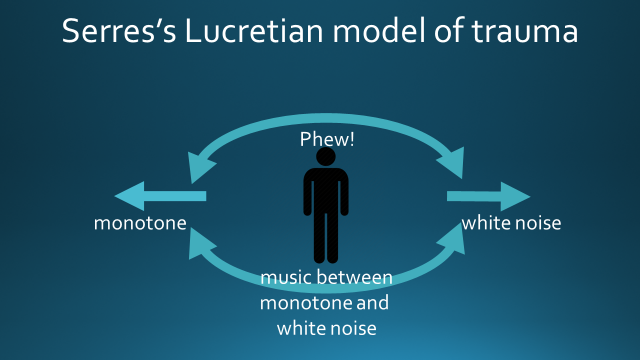

- In Serres’s understanding of trauma and meaning, which he derives from the ancient atomist philosopher Lucretius, rather than the structure of the overwhelming a-linguistic Real and phantasmatic frame that makes sense of it, has three elements: monotone and white noise as two ends of a spectrum, and meaning in between them:

So what is at stake for Serres is not merely taming the chaos of the Real, but existing in the tension between two equally hostile and chaotic poles:

Now there are indeed two kinds of chaos, the cloud and the pitcher. In the first image, multiple aleatory collisions within the infinite void of space send disordered atoms moving in all directions. In the second image, against the second background, encounters and collisions are not possible, and the laminar atoms move only in one direction. Disorder might be non-sense, but the only information that I can draw from chaos is that the innumerable and countless multiplicity either dissipates in all directions, or flows in one direction. […] There is no sense when everything has the same sense. There is no sense when everything is in all senses[22]

Crucially, this also means for Serres that there is no absolute split between language and the a-linguistic. For Lucretius, atoms are letters and there is no basic division between the Real and the symbolic as there is for Lacan. Meaning, for Serres and Lucretius, is not something introduced by language; it is incrusted in the joints of the universe:

Sense is an integration of small changes in sense. Against the white noise a signal appears, a bifurcation appears in the laminar flow. Sense is a bifurcation in the unequivocal. […] If there is just a single sense, then there is no sense. This is true of space and true of time: if there were only one season there would no seasons, if there were only one era there would be no eras, if there were only one island certainly there would be no island. And so on. It is true of movement: when there is just one uniform movement, in one direction, it is not perceptible. When everything moves, nothing moves. A change in sense, no matter how small, introduces sense.[23]

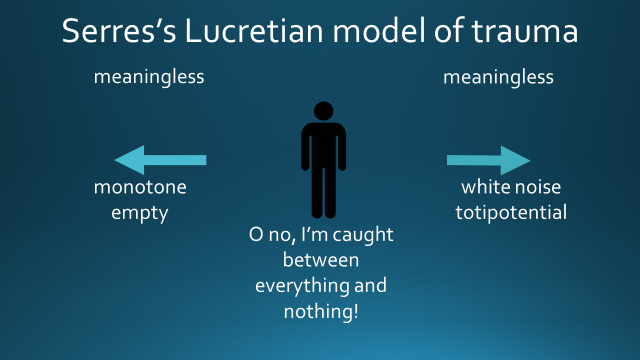

So what would trauma be in this model? Trauma is a loss of the middle ground, and this is more complex than Lacanian trauma. Both monotone and white noise overwhelm; both emptiness/void and overload, both nothing and everything without distinction are equally disorienting. This, I want to argue, is exactly what we see in Bleu, and it makes much better sense of the awkward moments that the Lacanian readings struggle to cope with.

For this model there are two instances of chaos and disorientation, not one:

Everything comes from the two instances of chaos that mark the two thresholds of disorder. The monotone unity of meaning, nothing new under the sun, or the totality of the meanings in all places, where nothing is ever the same and everything is different, are non senses by lack or by excess, by absence and saturation.[24]

A key tenet of this model is that loss is not always to be identified with negativity and absence; potentiality and freedom itself (understood as the potential to become) can also be painful. Trauma is not simply a symptom of loss and absence; it is also a reaction to pluripotency. We can long for—and mourn the absence of—the comfort of determinacy and limit just as much as a lack of freedom.

So what the Lacanian approach reads as just absence or loss, Serres’s Lucretian approach double codes as both loss and potentiality, both too little and too much. And what Julie experiences in the film is not just loss but increased potentiality. Before the tragedy her life is mapped out, her choices have been made. What she experiences with the loss of her family, however, is a sudden opening up of possibilities, like an increase in white noise. Her options are suddenly much greater than they were. She has become what Serres would call “dedifferentiated” or “incandescent”. The idea behind incandescence is of something glowing white. White light contains all the colours within it, as Newton’s prism experiment shows. The French “blanc” means both “blank” (nothing) and “white” (all the colours, everything together). This is Serres’s model of trauma.

Let us now take this Serresian understanding back to the film, and see how it can be useful in making sense of the key moments I identified earlier.

Waking from trauma

Look at the image below. It is what Julie sees on waking in hospital:

We don’t think “this is nothing”. We think “this could be almost anything”. It is not absence, but white noise. Perhaps we have all experienced that moment when we wake up and, for a moment, before we remember where we are, we could be anywhere. It’s not a moment of blankness but of pluripotency that needs to be resolved. In fact, we have a direct use of white noise a little later in the film, when the broadcast of Julie’s husband’s funeral fades not into absence but into pluripotent chaos:

These moments do not evoke loss and absence but potentiality and overdetermination, like the Rorschach shapes used in psychological tests:

A Serresian reading of the moment of waking up has Julie tottering between too much and not enough, between the white noise of pluripotentiality and the monotone of absence:

Everything comes from the two instances of chaos that mark the two thresholds of disorder. The monotone unity of meaning, nothing new under the sun, or the totality of the meanings in all places, where nothing is ever the same and everything is different, are non senses by lack or by excess, by absence and saturation.[25]

Silence and emptiness

Julie’s retreat into herself is not into silence and emptiness, but to an original chaos, to the white noise out of which life and information emerge. Throughout his work Serres uses a word that describes this original chaos from which meaning emerges. It comes from the first chapter of Genesis in the Bible:

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.[26]

The Hebrew for “without form and void” here is transliterated into both English and French as “tohu bohu”. Serres uses this Hebrew term to describe the origin of meaning and sense. I have translated one extended passage for you here from a recent book because I think it could have been written especially for Julie in this film. As I read it, think of Julie’s experiences:

I dive into myself, eyes closed, alone, mute, transformed, struggling to be attentive, I arrive at a deep bedrock, below memory, emotions and feelings, where I feel the functioning of my organs directly and apart from language, the vital warmth, I would die of cold without it; ice kills; we die shivering. My blazing body dives and swims in a warm fog. Even through the silence of health I can discern, coming from these lively, disordered sparks, a sort of tohu-bohu that in a way resembles the tinnitus with its vibrating surface that has been dogging me all these years, a hubbub doubtless produced by the effervescence of the admirable network of nerves and vessels, by the energy exchanges that delight the organs, tissues and cells, following billions of biochemical programs. From the Brownian movement of this living heat there emerges a chaotic background noise, both continuous and discontinuous. Its first hot rumblings give off primordial cries, the senseless calls and clamours of intimacy, barely audible. Can I call this deaf hubbub ‘unconscious’, where temperature is transformed into an acoustic cloud? […] Sometimes, out of this chaotic tohu-bohu and its fluctuations, at the limit of my ‘consciousness’, out of this background noise and these tiny and imperceptibly shrill signals there can emerge the fragment of a faltering melody, unheard-of yet caught by my hearing: a hooting, lamentation, hymn, cantilena, song of sorrow, monotonous chant… It draws forth my tears or thrills me with tenderness.[27]

The tohu-bohu for Serres can be a place of tears and lamentation, a “blanc” chaos of all emotions, all possibilities.[28] When we retreat inside ourselves it’s not to silence but to the tohu-bohu of the world, of creation.

Music

Serres’s Lucretian account of meaning also gives a wonderfully coherent way of understanding the music in the film. Music is not the weak point of the film or just ironic, but a figure for the murmurings and rhythms that Julie finds when she retreats within herself. Music draws us back to the original mixture, the apeiron:

Music leads us back to this primordial soup that the Ionian physicists once called the limitless indefinite when they observed or thought its cosmic figure.[29]

The music in Julie’s head is not merely a flashback to the trauma and a repetition compulsion; it is an attempt to rhythm existence again. Music sits between monotone and white noise, as a way of mediating between the two tendencies of utter predictability and utter chaos. Music “intrudes” not as a figure of loss, but of potency and potentiality.

The music, then, is not relegated to an unfortunate mis-step in the film but takes a much more central role in modulating between monotone and white noise, keeping Julie not from the single threat of absence but from the twin dangers of monotone and white noise, from blankness and from everything at once.

Synaesthesia

This way of understanding trauma also helps us better grasp the place of synaesthesia in Bleu. Rather than seeing it awkwardly as something that brings isolation, when in fact it is about breaking down boundaries and limits, Serres helps us to understand it as a return to the primordial mixing of what only later becomes distinct. Babies experience the world synesthetically, and synaesthesia in the film is a regression to first experience, to the time when everything was potential and nothing was decided yet. Evans and Wilson do acknowledge this aspect of synaesthesia in their treatments of Bleu:

Developmental synaesthesia (lifelong experience of the condition) is believed by some neuroscientists to be the unusual persistence of sensory mingling experienced by all newborns (Maurer 1997). This understanding offers a new and individualized twist to Emma Wilson’s application of Kristeva: ‘all colours, but blue in particular as the first colour perceived by the child’s retina, take the adult back to the stage before the identification of objects and individuation’ (Wilson 1998: 349). Julie is returned to infant modes of sensory fusion, signifying the strangeness and incomprehensibility of the world into which the car crash hurls her so violently.[30]

The swimming pool

Next, Serres’s Lucretian account of meaning gives us new ways of reading the swimming pool scenes. Let us begin by returning to Genesis 1:1-2:

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. 2 The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters.[31]

In these verses, water is a figure not of absence but of burgeoning possibility, not a motif of loss but of indeterminate, pre-formed chaos. Water is not a place of limits but a milieu where we can move in any direction, up and down as well as left and right; it is a place of omnidirectionality.

So Serres’s idea of the tohu bohu provides a reading not only the music in Bleu but also the swimming pool and the synaesthesia. It makes all these elements of the film cohere, and saves us from following Žižek in the knee-jerk opinion that any one of these elements is a misstep and out of place in the film. It also saves us from having to argue that synaesthesia, a condition of making links and drawing proximities, is a symbol of isolation, and the music about European unity is simply an irony.

The trauma in the film is not simply one of absence and loss but of the unity and mingling of primordial experience, and we can now read Julie’s experience in the film as a return to this de-differentiated state.

We can summarise these two interpretations in a table, which also serves as a conclusion of how Serres opens up for us a new reading of Bleu:

| ‘Trauma as loss’ interpretation | Serresian interpretation | |

| What is trauma? | exposure to an a-linguistic Real outside the phantasmatic frame | concurrent presence of monotone and white noise without any mediation |

| Effect of trauma | Disgust, absence, emptiness | Simultaneous absence and |

| Julie’s experience | Denial, emptying, absence | Both monotone (absence) and white noise (chaos) |

| The colour blue | lack, aching absence, isolation | Bridges inside and outside, makes links |

| waking from trauma | abstract freedom, pure self-relating negativity | pluripotency |

| Music | Echoes in spaces of denial | Transgresses limits and borders; takes us back to “primordial soup”, mediates monotone and white noise |

| Swimming | Absence, abstraction; drown her memory | Isolation but also tohu bohu, original potentiality |

| Synaesthesia | Detachment, isolation | communication, pluripotency |

[1] Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) 3.

[2] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 169.

[3] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 169.

[4] Joseph Kickasola, The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski: The Liminal Image (New York: Continuum, 2004) 264. CW’s emphasis.

[5] Emma Wilson, “Three Colours: Blue: Kieslowski, colour and the postmodern subject”, Screen 39:4 (1998) 352-3.

[6] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 175.

[7] Emma Wilson, “Three Colours: Blue: Kieslowski, colour and the postmodern subject”, Screen 39:4 (1998) 351.

[8] Emma Wilson, “Three Colours: Blue: Kieslowski, colour and the postmodern subject”, Screen 39:4 (1998) 354.

[9] Georgina Evans, “Synaesthesia in Kieslowski’s Trois couleurs: Bleu”, Studies in French Cinema 5:2 (2005) 84.

[10] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 164.

[11] Emma Wilson, “Three Colours: Blue: Kieslowski, colour and the postmodern subject”, Screen 39:4 (1998) 351.

[12] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 171.

[13] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 176.

[14] Emma Wilson, “Three Colours: Blue: Kieslowski, colour and the postmodern subject”, Screen 39:4 (1998) 3534.

[15] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 203n52.

[16] Georgina Evans, “Synaesthesia in Kieslowski’s Trois couleurs: Bleu”, Studies in French Cinema 5:2 (2005) 81.

[17] Georgina Evans, “Synaesthesia in Kieslowski’s Trois couleurs: Bleu”, Studies in French Cinema 5:2 (2005) 78.

[18] Georgina Evans, “Synaesthesia in Kieslowski’s Trois couleurs: Bleu”, Studies in French Cinema 5:2 (2005) 81.

[19] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 176.

[20] Marek Haltof, The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski : Variations on Destiny and Chance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004) 126.

[21] Slavoj Žižek, The Fright of Real Tears: Krzysztof Kieślowski Between Theory and Post-Theory (London: BFI Publishing, 2001) 113-4.

[22] Michel Serres, The Birth of Physics, trans. Jack Hawkes, ed. David Webb (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2000) 144-5.

[23] Michel Serres, The Birth of Physics, trans. Jack Hawkes, ed. David Webb (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2000) 145,6.

[24] Michel Serres, The Birth of Physics, trans. Jack Hawkes, ed. David Webb (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2000) 146.

[25] Michel Serres, The Birth of Physics, trans. Jack Hawkes, ed. David Webb (Manchester: Clinamen Press, 2000) 146.

[26] The Bible: Genesis 1:1-2.

[27] “Je plonge en moi-même, yeux fermés, solitaire, muet, converti, attentif avec difficulté, j’accède à un socle bas, sous les souvenirs, émotions ou sentiments, où ma cœnesthésie ressent, directement et sans langage, la chaleur vitale, je m’évanouirais de froid, si elle s’absentait ; la glace tue ; nous mourons de grelotter. Brûlant, mon corps plonge et nage dans un brouillard chaleureux. Même à travers le silence de la santé, je crois percevoir, émané de ces flammèches vives en désordre, une sorte de tohu-bohu qui ressemble, en quelque façon, aux acouphènes dont la nappe vibrante m’assaille depuis des années, brouhaha issu sans doute de l’effervescence produite par le réseau admirable des nerfs et des vaisseaux, par les échanges d’énergie auxquels s’adonnent les organes, les tissus et les cellules, selon des milliards de programmes biochimiques. Du mouvement brownien de cette chaleur vivace émerge un bruit de fond chaotique, discontinu et continu, dont les premières rumeurs, chaudes, émettent les cris originaires, appels et clameurs insensés de l’intimité, aux limites de l’inaudible. Puis-je nommer inconscient ce brouhaha sourd, où la température se transforme en nuage acoustique ? […] Parfois, de ce tohu-bohu chaotique et de ses fluctuations, à l’orée de ma « conscience », de ce bruit de fond et de ces signaux menus, imperceptiblement aigus, peut surgir un fragment de mélodie timide, inouïe et venant à l’ouïe : hululement, lamentation, hymne, cantilène, complainte, mélopée… Elle m’arrache des pleurs ou m’exalte de tendresse”. (Michel Serres, Récits d’humanisme (Paris: Éditions le Pommier, 2009) 46-8).

[28] Michel Serres, Récits d’humanisme (Paris: Éditions le Pommier, 2009) 115-6.

[29] “La musique nous ramène à cette soupe primitive que les physiciens d’Ionie appelaient autrefois l’indéfini sans limite quand ils observaient ou pensaient sa figure cosmique” (Michel Serres, L’Hermaphrodite: Sarrasine sculpteur (Paris: Flammarion, 1987) 129).

[30] Georgina Evans, “Synaesthesia in Kieslowski’s Trois couleurs: Bleu”, Studies in French Cinema 5:2 (2005) 79.

[31] The Bible: Genesis 1:1-2.